In the first part post (5 years ago...yes!), I talked about some refreshing visions on IT industry. It was quite rhetorical, now it’s time to illustrate with real examples from my experiences. 5 years later, sadly, I just have more examples...

The mainstream organisation is still quite far from Features Team, collocated teams and all other concepts that were proposed early by Agile advocates (and even Lean before Agile...). Even if Agile is more and more popular, it is often interpreted just as a method, missing crucial aspects.

So let's try to dive in details of these organisations, but I will not mention specific to avoid defamation.

Stereotypical mainstream organisation

First, I would like to expose a stereotypical mainstream organisation that illustrate use of hyperspecialization for an application development (I have already worked in contexts like that). Here are a non exhaustive list of services that would "collaborate" in these kind of organisation:

- users (they don’t know what they need exactly, don’t complain about it: you have to build adaptable solutions through quick feedback)

- business analyst team (produce specifications more or less related to something that could be developed and not in phase with “real” user needs, i.e what would make users happy in the end, not what they requested at start...)

- architecture (often in an “ivory tower”, dictates several constraints, and in worst case, it could be several different teams: security, urbanism, functional architecture, application architecture, IS architecture, technical architecture…)

- X project dev team (“just” write code for new features on project X)

- maintenance dev team (“just” write code for bug fixes, far more cheaper => do not bother project dev team with that!)

- level 1 support (don’t want to eliminate “waste” their work are based on, see http://bit.ly/pE8h8N)

- level 2 support (same bias as level 1)…and many more levels in worst cases

- test team (will not try to automate tests: same bias as support…)

- dev tools organization (as complex as previous one for each tool !): standards and norms are the rules! Then impossible to customize anything according IT teams' needs

- many teams for operations (often too specialized themselves also…)

I agree that it is often a mix or subset of this organisation that you will find in companies. Also, I tend to notice that the bigger companies are the most mono-specialized services you have, and the same with big projects (that's another subject, but big/huge projects should be avoided...or more exactly functionaly splitted...).

Note I know that there are also some constraints that could be required by regulation authorities or encouraged for responsibility segregation principles (for security or to void conflicts of interests for example). By the way, hyperspecialization is not required.

About "mainstream" qualification, we could argue (out of scope for this post)...even with Agile being more and more usual.

And then, what are the problems?

Yes, you can ask this question...and in few words, I would say these organisations are based on lots of biases.

The more you have different teams in your organisation, the more you will need coordination. I saw an interesting talk from Alexey Krivitski at LKFR2016 (waiting for video). Also, it is very common each team has its own goals, it may lead to misalignment and local optimization (see system thinking). A good way to experiment this is to play the Beer Game.

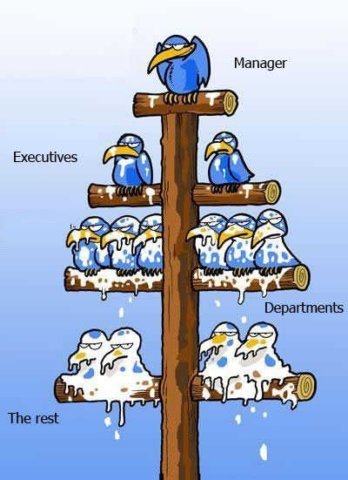

As there are more managers for all these teams, there are more managers on top of them, leading to quite big hierarchy. Managers are then more often in "command and control" mode, they mostly focus on non-operational topics: giving on-the-shelf solutions, transmitting standard recommendations...and it leads to teams that execute processes without thinking about improvement or innovation. I recommend reading Lost in management books (in French sorry) with lots of insights about management from sociology perspective.

The more frightening to me is that lots of people often ask for specialization. They have been used to not innovate or do by themselves, it is easier to ask someone else to do the job.

Last, I regret that Conway's law applies quite well: the information system reflects the organisation. It means that in these organisations you will have information system with heavy processes, not ready for change, if not mostly frozen once delivered...

So, what can we do?

For sure, even if I don't rule that out, I don’t (sometimes I do!) want to install my workstation and servers supporting VMs, nor administrate network, nor install databases clusters...but hyper-specialization leads to an extreme where your are finally responsible of something so tiny, that you become responsible of nothing...and in a land of "everyone responsible of nothing", it becomes a nightmare! Changes are very slow because it involves lots of people and again individual goals are not aligned and produce waste in the global process...

Agile community propose collocated teams, composed of specialized members. But I tend to see that it is too often interpreted as gather hyper-specialized people in a single team and that's it! Sorry but I don’t see how you could have a team with one member specialized on each function...how do you "feed" constantly each function with the same amount of work? How do you do when one of the function is overloaded? It seems to me completely counter-productive and against lean spirit. Note I am not talking about searching for 100% time allocation, that's not a goal I support.

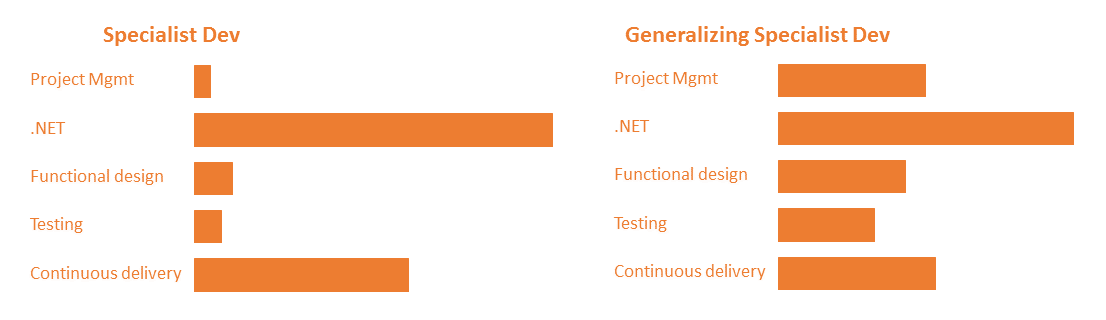

I think generalizing specialist concept is a good way to benefit from existing specialities of some people and to leverage skills of others through a Learning Organization. And it means people must be are aware of the fact they will need to go out of their confort zone. It is probably one of the most difficult thing, because it is about people and their willing to change things. Note I am not saying that people do not like changes (as it is often heard), I prefer to say that they prefer to avoid changes in context they cannot trust...and it is radically different. Everyone in the team have to ensure trust is shared, to build a security zone where errors will be seen as feedback to improve and not as failures. If you miss that point, then you will have people who do not want to change.

Note that there is still another bias: lots of people are more and more used to distrust, because they have encountered more distrust than trust in their day to day life. That's why, even if a team choose to try more trusty environment, it will not emerge by itself in one day (not even in a week or a month), it will take time to take root. Also, deciding (top-down) that trust must be the norm cannot work, if team members do not want to try, there will be lots of pain points.

Example of the "best" team organisation I met

The way we applied this in one of my previous team was: everyone was responsible from business need elicitation (with users directly, users' proxy – Marketing team – more exactly) to delivery of bugs fixes and features, including support at level 2 (level 1 is done by users' proxy). So each team member worked on business analysis, development, part of tests (unit, integration and functional ones, mostly automated).

Giving the problems encountered with dev tools organisation, we had our own server with our own dev tools (not so hard and secured at best we can). With this organisation, we were often slowed by some counter-productive activities (like support level 2, manual tests, regressions due to bad testing...), so we were motivated to reduce them in order to maximise time allocated for activities that bring values to business.

This organisation led us to more adaptable software since we were always searching a way to improve. Since we had ownership of most of the processes, we were able to change and adapt them to the context. The need of coordination was reduced at its minimum, then responding to change was quicker and costs were quite low compared to other "classic" teams.

A final word on this team is that it is quite difficult to find people that are ok AND able to work this way. Too many people consider that as a developer we should develop 90% of the time, but in these kind of organisation, you will develop around "only" 50% of the time, and it's alright. It reminds me some tweets from Mathias Verraes (7 tweets, but I mention my best two):

1/7 Many programmers think of all activities that are not coding as "not real work". Meetings, documenting, even modelling on a whiteboard.

— Mathias Verraes (@mathiasverraes) January 5, 2017

6/7 This is why I reject the "Always Be Coding" mindset. Instead of just building, spend time on retrospection on what & how to build.

— Mathias Verraes (@mathiasverraes) January 5, 2017